In 2009, Halton Regional Police Service received their federal license from Transport Canada and started the process of building out a drone program. They were just the third agency in North America to do so, and Andy Olesen was there leading the way for his department.

“We started to use drones when I was part of the marine unit,” said Olesen, whose career in public safety has spanned 30 years. “This meant working on the waters of Lake Ontario. During search and rescues, we often had to call for military helicopters to conduct the search. Helicopters being what they are, are expensive, and they’re not always available. So, we were looking for other options. We saw that the Ontario Provincial Police had just started using drones in Kenora. I contacted Marc Sharpe who was the operator there and one thing led to another and within about a year we had acquired our first system through a Defense Research Department Grant.”

Olesen then went on to not only help deploy drone programs for the Search and Rescue Team and the Explosive Chemical, Biological, Radiological, Nuclear (CBRN) Response Team but also to help form the Canadian Emergency Responders Robotics Association (CERRA).

“We formed CERRA about two years ago,” explained Olesen. “The reason we formed it was we felt that most organizations out there focused on the commercial side of things, whereas we thought there was a specific need and requirement in public safety. Additionally, these groups often focus mainly on aerial applications, but we felt there is a need to include ground and water robotics. We think that aerial, ground, and water robotics will cause a big shift for public agencies, especially when these systems are able to work together. We need to provide support for agencies looking to adopt them.”

Drone Network News got to speak to Olesen about his experiences in search and rescue and CBRN, and get his thoughts about the future of public safety including drone as a first responder, autonomous robotics, and the challenges with keeping up with data and the speed of technological innovation for agencies.

Drones in Search & Rescue

“Everyone reads about missing people all the time, but there’s a very methodical and organized process to conducting a search. It’s not just a question of sending people out, there is a method to it,” Olesen began when asked about his work in search and rescue. “It involves a lot of people going into potentially hazardous areas or covering large terrain.”

The process can take search and rescue teams over water, rural and urban areas, and even along public transportation lines like trains—each present their own challenges for conducting a search on foot.

“For example, if you have to search railway tracks, you may have to slow down or stop trains to conduct the search,” explained Olesen. “Anyone who is involved in transportation knows that if you slow or stop the trains in one area it has a huge ripple effect, not just for the region but all across North America. So, to have a drone that can fly along the railway tracks looking for somebody means we don’t have to stop the trains. Additionally, we can send people to other areas to search, enabling us to expand our search radius more quickly. That drone might not find somebody, but they are providing a safer alternative and freeing up people to go to other areas to continue that search.”

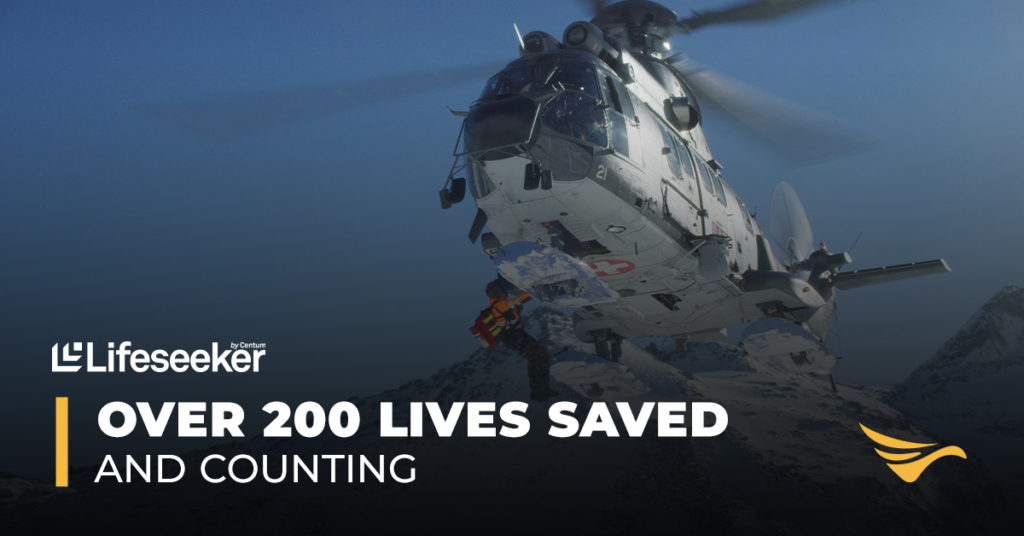

These capabilities are incredibly helpful in rural and urban search and rescue, but they are particularly useful for water search and rescue, when time is of the essence.

“With water searches, especially when searching large bodies of water, it can take time just physically getting a boat from point A to B and sometimes you are dealing with bad weather or ice,” he said. “If you can get a drone up 100 to 200 feet, you have a much bigger area to view. Drones are capable of not only finding people but in some cases, delivering lifesaving equipment, whether it’s a life preserver, providing the ability to communicate, or just lighting up an area so that that person can be identified. In many cases, it’s just speed, it’s efficiency, it’s a safer way to do it, whether it’s on its own or in combination with other current techniques. The same holds true in rural and urban areas, where sometimes you have to cross large bodies of water or wooded areas, it takes time. Aerial systems can obviously cover that ground much quicker and much safer.”

The stories we hear today of how drones have helped in search and rescue are ubiquitous, thanks to the initial efforts of individuals like Olesen and agencies like Halton Regional Police. But Olesen has also been integral in using drones and robotics in an emerging use case: the assessment of explosive and potentially harmful agents.

Drones Being Used by Chemical, Biological, Radiological, Nuclear Response Teams

A call is placed to an emergency call center, a tractor trailer truck carrying an unknown substance has tipped over on a major highway or a building has been evacuated because of a suspicious package. The police arrive on scene and need to assess what the substance is and if it is hazardous. This is when the Explosive Chemical, Biological, Radiological, and Nuclear (CBRN) Response Team comes in. In the past, this usually meant suiting up in protective gear and heading into the hazard to assess what was there. Today, robots are playing a much bigger role, especially as sensors are becoming smaller and more compatible with drone systems.

“In the last few years, these systems have evolved leaps and bounds,” stated Olesen. “Early on the detection equipment was heavy and needed a large drone, which prevented us from getting close, so we mainly used the drones to get images of a scene to know what we were dealing with and if we could get a ground robot in. Now they’re developing detection equipment that can be carried by drones that can get inside vehicles and buildings, and the mapping has increased tenfold. Responders can now record a scene, map it and do measurements on site or develop a 3D model with LiDAR for scene reconstruction.”

These systems have become vital tools to protect the safety of everyone called in to investigate these types of scenarios and are only going to become better in the future.

Outlook for the Future for Drones in Public Safety

When looking at the future of public safety and robotics, one of the most exciting developments on the horizon according to Olesen is the widespread use of Drones as a First Responder.

“The idea to be able to launch a system from a building and get to a scene fast and record the situation is invaluable, and that is what Drones as a First responder (DFR) is able to do,” began Olesen. “For example, you could have three different witnesses call in a collision and each one can give very different stories. If you can get an aerial system there, get pictures of what is really happening that is very valuable to police, fire, and EMS from multiple perspectives. A fire department might see something different than a police officer or emergency medic—they are each trained to look for different things—now you can send them all a detailed set of pictures, and they can know exactly what is going on at the scene. There are a thousand different things that a picture can do because it doesn’t rely on translation or someone reading through pages of text that can be misinterpreted. A picture is truly worth a thousand words.”

But Olesen pointed out that applications like this also comes with their own challenges. As drones and other robots are deployed autonomously for things like Drone as a First Responder, there could be an unintended impact on how people respond to having a drone instead of a human arrive on scene. This is why he is supporting research on how humans in crisis situations respond to autonomous robots.

“The engineering students at McMaster University are studying the dynamics of using autonomous systems from the human perspective,” explained Olesen. “For example, if a victim was in a car wreck and saw a drone or other robot coming up to them to help instead of a person, how would they react? The results of this study will help us better understand how robots impact outcomes. Will the response be the same, better, or worse, especially for those in critical conditions? Does engineering design matter in these scenarios? We need to find out this and more as we move forward with these applications.” Olesen hopes that this will help inform how drones are used in emergency response situations. As he continues to support research on how the use of robots will impact outcomes, he remains positive and excited about the innovation he sees and its potential to improve emergency response—as long as regulations, humanity, and public safety can keep up and adapt to these rapid changes.